What do secondary students think about AI?

Excerpt from Thematic Analysis study A. More (2023)

In my classroom, discussions about AI are a regular occurrence. The students I teach now commonly use 'chat' as a verb to describe their interactions with large language models like ChatGPT. At first glance, this might seem like a subtle shift in language, a new term adapted by Gen-Z for their ease. However, upon closer examination there appears to be a wider story here, one I feel is worth sharing.

The arrival of AI at such a pace marks an ontological shift as it challenges the very foundation of human existence, agency and identity. Our children feel this ‘shift’ too, but their voices often go unheard at the expense of the adults in the room. In educational arenas globally, there is no shortage of adults sharing their opinions about AI, from the progressive evangelists making bold predictions to the cautious observers. AI is omnipresent and appears to have established a lasting presence.

How often do we ask children about what they think about AI?

Against a lively backdrop of commotion surrounding AI, children listen from the sidelines as discussions unfold about how AI could impact their future careers, automate aspects of their lives, and potentially pose threats. They are attuned to these conversations, yet frequently find themselves excluded from these critical dialogues, or key strategic decisions. As an educator with a passion for AI research, this is the dynamic I am trying to change. In 2023, I embarked on a research journey to explore AI through the hearts and minds of the students I teach. I was particularly curious to find out how children view AI in terms of what it offers them, but also, what it takes away.

What does technology want?

This is a great question, and one we should ask ourselves regularly. I first discovered it in Kevin Kelly’s 2011 book of the same name, and have been grappling with it ever since. Essentially, technology wants something from us - whether that is your inbox wanting to be emptied, or your chosen LLM interacting with you - technology only has a purpose if we need it, and use it. If we shift this to the child for a moment - they have different needs to adults. They see technology as a way to connect to others through interaction and experience. If you have ever seen a child using technology you might have witnessed a symbiosis between the human and the machine as they seamlessly integrate it into their daily lives. AI is no exception.

As a pre-VIVA exercise, I wanted to explore some of the ideas above in more depth. I was hoping to shed some light on what children really think about AI in relation to their lives, learning and collective futures. As a teacher, and a researcher immersed in the field - I chose Dorothy Smith’s Institutional Ethnography (IE) as a way to make the ‘everyday interactions with AI more visible’. This method combines theory and practice to clearly reveal how AI is incorporated at school and how the institution itself handles it, connecting daily school life with broader societal trends. Epistemologically, this was a way to bring AI into contact with something I care deeply about - student voice.

It matters which voices are heard, and why?

Student voice is far more than the uttering of words. It can be a transformative force for change, but is often met with resistance due to the coercive power dynamics it has come to represent. Let’s unpack this a little. In 2012, when writing about student voice, Fielding said ‘we need to reflect on the nature and extent of the silences that so often go unnoticed and unrecorded.’ In the two decades that have elapsed since, the children of today face new challenges that threaten to transform the texture of learning, yet their agency to discuss this is falling away. Despite this, schools still use student voice as a management tool, or an instrument to enforce accountability measures from external forces (inspection regimes or performance management). As a result, teachers see the process of ‘collecting student voice’ as something that is ‘done’ to them - rather than ‘with them’. These tensions illustrate how ‘student voice’ has been leveraged to become a consumerist ideology rather than a democratic right.

The work of Michel Foucault is an obvious reference point for studying power dynamics within an institution. In Discipline and Punish, Foucault (1975) explicitly refers to schooling as an apparatus of modern disciplinary power. Foucault depicts the human body as docile within institutions. Such ideas have clear relevance to practices in schooling, and indeed, parallels around ‘who holds the power’ and ‘truth telling’. Student voice, and the resulting epistemological framework that supports it disrupts the traditional power dynamic as it invites the child in, allowing the teacher and the student to co-construct knowledge together.

Unlocking Themes: Thematic Analysis as a Methodological Tool

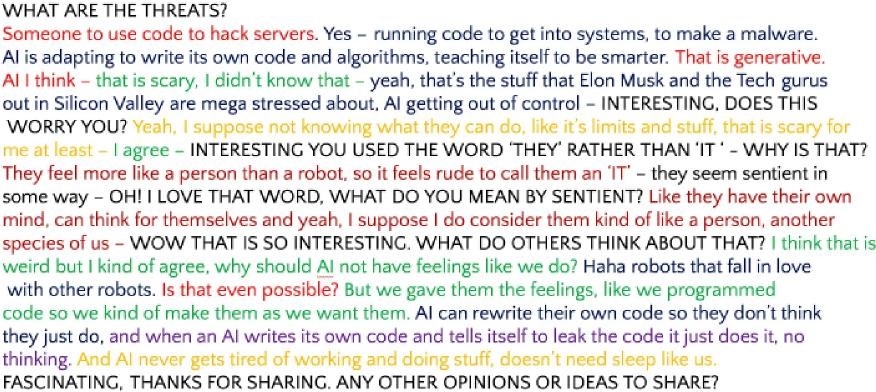

Adopting Braun and Clarke’s (2006) Thematic analysis allowed me to identify and interpret patterns and themes within the data set. I set about interviewing groups of students, aged 11-14 years, using a semi-structured format to see where the conversations took us. The resulting transcripts were time consuming but as the initial codes started to become themes - the process warranted the effort. The narrative that unfolded surprised me given the questions I had posed.

As a rule, thematic analysis requires the researcher to identify underlying themes. After exploring the surface meanings of the data I started to see the underlying ideas, assumptions and ideologies emerge. The resulting analysis after all six stages revealed three overlapping themes:

-

Power

-

Identity

-

Acceptance

At this stage I needed the analysis to go beyond the explicit meanings to explore the underlying ideas, values, and frameworks that may indirectly shape or inform what is said. In Thematic analysis, the distinction between semantic and latent themes lies in the depth of analysis: semantic analysis stays within what is explicitly stated, while latent analysis seeks to uncover what is unsaid or taken for granted within the data, offering a deeper, often more critical interpretation. This is what I was searching for.

Final themes

- Students refer to AI as ‘them’ and ‘they’ rather than ‘it’.

- Teachers are here to stay, no robot teachers.

- AI should ultimately make us better at being human.

Each theme speaks to how children see AI in their world. These themes tell us a story if we are brave enough to listen. Firstly, students repeatedly used ‘they’ to describe AI - hinting at how they perceive the identity of this emergent technology pointing the compass towards posthumanist ways of thinking. Students value the human teacher and see a replacement in any form as an abstract concept. To elaborate, they do not see an AI-teacher as a sensible idea as they feel it would lack empathy and understanding. One excerpt from the transcripts illustrates this point:

Child Q: So, if ! came into school in the morning sad because my dog died. How would the A! know this and know to be kind? A human teacher would understand and be nice to me.

I won't claim that students explicitly used terms like 'sentience' and 'consciousness,' but they certainly alluded to them indirectly.

The final theme gave me hope as it talks about what makes us uniquely human, and how the arrival of another form of intelligence should make us hold a mirror up to what makes us uniquely different. Taken together, the findings intrigue me, and leave plenty of scope to explore further, perhaps at the VIVA stage.

Where to go next?

While the field of student voice is relatively settled, the rapidly evolving AI domain still lacks a robust, evidence-based foundation. Merging these areas highlights a clear research gap by bringing student voice into contact with AI.

As teachers grapple with what AI is, and school leaders attempt to domesticate it - it seems fitting that we invite students to share their views as they are the main actors in the process of learning. Regarding the uncertain future of this technology, I find myself both cautiously intrigued and eager to discover its true intentions. I think young people could teach us some valuable lessons here. Afterall, they will inherit this future we adults speak of so often.

I still can’t answer the question ‘What does technology want?’ but through the eyes of the students I teach, I am starting to see what AI as an emerging technology offers us, but also, what it might take away. As a teacher, I take comfort in knowing that my students don't plan to replace me yet - though I'm keeping an eye on the quieter ones, just in case.

References

Braun, V & Clarke, V 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. Vol. 3 (2)

Fielding, M., 2012. Perspectives on Student Voice. Patterns of Partnership and the demands of deep democracy.

Foucault, M., 1975. Discipline and Punish: The birth of the prison. Penguin Kelly, K, 2011. What technology wants. Penguin books

Smith, D., 1987. The Everyday World as a Problematic: A Feminist Sociology. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press

The content expressed in this blog is that of the author(s) and does not necessarily reflect the position of the website owner. All content provided is shared in the spirit of knowledge exchange with our AIEOU community of practice. The author(s) retains full ownership of the content, and the website owner is not responsible for any errors or omissions, nor for the ongoing availability of this information. If you wish to share or use any content you have read here, please ensure to cite the author appropriately. Thank you for respecting the author's intellectual property.

You can find a suggested citation here:

More, A. (2024, December 13). What do secondary students think about AI? AIEOU. https://aieou.web.ox.ac.uk/article/what-do-secondary-students-think-about-ai